Why Its Imoortant for Seniors to Have Medication Review

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

An inventory of collaborative medication reviews for older adults - evolution of practices

BMC Geriatrics volume 19, Article number:321 (2019) Cite this article

Abstruse

Background

Collaborative medication review (CMR) practices for older adults are evolving in many countries. Development has been under fashion in Republic of finland for over a decade, just no inventory of evolved practices has been conducted. The aim of this written report was to identify and describe CMR practices in Republic of finland after 10 years of developement.

Methods

An inventory of CMR practices was conducted using a snowballing approach and an open phone call in the Finnish Medicines Bureau's website in 2015. Information were quantitatively analysed using descriptive statistics and qualitatively past inductive thematic content analysis. Clyne et al's medication review typology was practical for evaluating comprehensiveness of the practices.

Results

In total, 43 practices were identified, of which 22 (51%) were designed for older adults in primary intendance. The bulk (n = 30, seventy%) of the practices were clinical CMRs, with 18 (42%) of them existence in routine use. A checklist with criteria was used in 19 (44%) of the practices to identify patients with polypharmacy (north = 6), falls (n = v), and renal dysfunction (n = 5) as the most mutual criteria for CMR. Patients were involved in 32 (74%) of the practices, mostly as a source of information via interview (n = 27, 63%). A medication care programme was discussed with the patient in 17 practices (xl%), and it was established systematically as usual care to all or selected patient groups in 11 (26%) of the practices. All or selected patients' medication lists were reconciled in fifteen practices (35%). Nearly one-half of the practices (n = nineteen, 44%) lacked explicit methods for post-obit upward effects of medication changes. When reported, the furnishings were followed up as a routine control (north = 9, 21%) or in a follow-up appointment (n = 6, 14%).

Conclusions

Unlike MRs in varying settings were available and in routine use, the majority being comprehensive CMRs designed for primary outpatient care and for older adults. Even though practices might benefit from national standardization, flexibility in their customization according to context, medical and patient needs, and bachelor resources is of import.

Groundwork

Polypharmacy and associated loftier medication costs usually occur within a small proportion of medicine users, a bulk of which are≥65 years old [1]. As polypharmacy is associated with increased hazard of medication-related bug, different medicines optimization strategies are required for various patients [i,two,3]. According to the National Institute of Health and Intendance Excellence (Prissy) in the United Kingdom (UK), medicines optimization is a person-centered approach to condom and effective medicines utilize to ensure that people obtain the all-time possible outcomes from their medicines [2].

Collaborative medication reviews (CMRs) are 1 of the methods in medicines optimization to prevent inappropriate medication use and to increase adherence [2, four,v,half dozen,seven,viii,ix,10]. CMR is an internationally recognized term referring to medication review practices involving pharmacists equally reviewers of the medication in close collaboration with other health care professionals. CMR practices differ within countries and internationally, for case by the context and the patient groups they are designed for, which healthcare professionals are involved, the caste of collaboration, and the degree of patient involvement in the process [5,6,7, 9, 11,12,xiii,14,15,sixteen,17,xviii,19,twenty,21,22]. Currently, CMR practices are under development in many countries, with the most show of affect on patient and service outcomes, for instance, the appropriateness of the medication and readmission rates, respectively, coming from pioneering countries, such every bit the Us, Australia, and United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland [5,6,seven, 9, 11,12,13,xiv,xv,16,17,18,19,20,21].

Finland has one of the most quickly crumbling populations in the world. Equally a consequence, resent Government Programs take focused on finding strategies for managing risks and costs in geriatric pharmacotherapy in outpatient and inpatient intendance [23, 24]. CMRs take been prioritized in the Government Program 2015–2019 for implementing rational pharmacotherapy every bit a part of substantial healthcare reform [25, 26]. Evolution of collaborative medication review practices was initiated in Republic of finland in 2005 as part of a national program aimed to strengthen community pharmacists' involvement in patient care [19, 27]. For that purpose, long-term accreditation training (i.5 years alongside work) for practicing pharmacists was initiated to attain collaborative comprehensive medication review competency [27]. Since so, CMR practices involving pharmacists and other health intendance professionals have evolved in outpatient and inpatient care [28,29,30,31]. Thus, Finland provides an example of a country with no previous history of patient-oriented clinical pharmacy practice where initiation of CMRs and related accreditation training have remarkably fostered remodeling the pharmacists part in patient care. Sharing experiences could be helpful in other countries seeking to evolve pharmacists' roles in a similar manner. Furthermore, Republic of finland has benchmarked advanced CMR practices in other countries, particularly in Australia and USA in the early phase of starting the CMR accreditation preparation in 2005 [19, 27]. Despite growing prove of the positive outcomes (the appropriateness of the medication and readmission rates, respectively) associated with CMRs [5,6,7, 9, 11,12,thirteen,14,15,16,17,eighteen,19,20,21,22, 32], there has not been a comprehensive evaluation of their implementation on a nationwide basis. Detailed descriptions of CMR procedures performed are important, as the intensity of their conduct and range of services provided (for example, prescription reviews vs. clinical medication reviews) might be associated with varying productivity, or caste of patient outcomes accomplished. The aim of this study was to identify and describe the state of CMR practices in Finland after 10 years of development.

Methods

Study pattern and setting

In seeking to create an inventory to depict the country of CMR practices in Finland, the researchers conducted a web-based open up call past the Finnish Medicines Agency (later Fimea) in Apr–May 2015. The call was targeted to all health intendance professionals involved in collaborative teams reviewing medications of older adults in any health care context. The inventory was office of Fimea's long-term program to promote rational medicine apply of older adults, and the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health funded a research project on medicines optimization for older adults (ILMA) [10].

Inventory instrument

The inventory musical instrument (Boosted file 1) was developed in four phases: 1) drafting the commencement version of the instrument; two) modifying the content of the instrument with help of the medication review experts; 3) modifying the instrument to cover all health care contexts; and 4) pilot testing the instrument.

Stage i

The commencement draft of the inventory musical instrument was adapted from questions previously used 1) by Fimea to investigate challenges and solutions in medication management of older adults [13], 2) by our research group in an inventory of medication review practices in European Wedlock (EU) countries [33], and iii) in a systematic review of CMR practices and their effectiveness in outpatient care [10]. The questions covering typical phases of a medication review process were the post-obit (See also Additional file i): 1) Where, how and by whom is a patient with medication-related problems identified? 2) Which health intendance professionals are involved in reviewing the medication? 3) How is the patient involved? 4) How do dissimilar health care professionals and organizations communicate patient data in unlike phases of the medication review process? 5) Where are the patient's medications reviewed (the site/venue and phase of the patient's intendance pathway)? 6) How is the actual review of the medications performed? 7) How is the follow-upwardly of implementing medication changes organized? viii) Is the practice based on whatever previous medication review procedure and/or theory? nine) What kind of tools are used in reviewing medications (electronic and/or manual)? and 10) What is the context of the practice? Additionally, the inventory solicited data on the medication-related issues reviewed, involvement of proxies in the medication review, and treatment follow-up practices in usual patient care.

Finally, the respondents were asked to indicate the comprehensiveness of their practice according to Clyne et al.(2008) [34], which is a National Health Service (NHS)-based categorization widely used in the Great britain and elsewhere as criteria for standardizing CMRs [13, 22]. It categorizes CMR practices into the post-obit iii categories: i) prescription reviews; ii) concordance and compliance reviews; and 3) clinical medication reviews. The categorization takes into consideration objectives of the review (addressing technical issues, the patient's medicines taking beliefs, and the patient's utilize of the medicines in the context of his/her clinical condition), the used patient information sources, medications reviewed (merely prescription medicines, both prescription and non-prescription medicines and other complementary products), and patient involvement in the review (not involved, usually involved or always involved). Respondents were asked to identify the comprehensiveness of their CMR practice past defining its purpose, i.eastward., whether it was for: ane) technical review of prescriptions / list of medications (i.eastward., prescription review); two) review of the prescriptions, the patient is involved to discuss medication taking and support adherence (i.e., adherence/cyclopedia review); or three) review of the medications in the context of the patient'southward clinical status (i.e., clinical medication review).

Phase 2

Six medication review experts from unlike wellness care contexts (hospital, community pharmacy and assisted living) and the Clan of Finnish Pharmacies (AFP) were consulted when forming the final inventory instrument. Questions related to patients and health care professionals' interest in the medication review procedure and in medication-related issues reviewed were modified co-ordinate to their feedback. New questions were added relating to post-obit up implementation of medication changes and involving proxies in medication reviews.

Phase 3

Questions were rephrased according to experts recommendations to enable to reflect on CMR practices in different contexts. Some open-concluded questions were also changed to structured questions to reduce response burden.

Stage 4

The inventory instrument was piloted for face and content validity and technical functionality by the aforementioned experts involved in developing information technology. Changes were modest at this phase, limited to wording and grammar, not content. The final inventory instrument is presented in Additional file one.

Data collection

The inventory was conducted using a snowballing approach and an open up call via the Finnish Medicines Agency (Fimea'south) website where the invitation letter with a link to the inventory musical instrument was openly accessible in Apr–May 2015. The link was also widely disseminated via practiced networks and mailing lists. Receivers of the invitation were encouraged to report as many CMR practices as they were involved in and to forward the link to their networks [35]. This data drove method was called, as no previous data or register was available well-nigh the CMR practices and healthcare providers involved in Finland. Two reminders were sent to the aforementioned receivers than the original link 2 weeks after opening the call (get-go and end of the calendar week). Responding was voluntary, and respondents did not receive any incentives. Responding to the survey was considered equally giving informed consent.

Data analysis

Data gathered by structured questions were quantitatively analyzed for descriptive statistics using frequencies and percentages by Statistical Parcel for the Social Sciences (SPSS-21) and Excel-program (2013). Open-ended questions (indicated in the Additional file one) were analyzed qualitatively by inductive thematic content assay, meaning that all themes arise directly from the survey responses [36]. The narrative responses were read, encoded and categorized into conceptual themes. The frequencies of appearance of each categorized theme in the responses were counted, and the results were presented as frequencies and percentages to obtain understanding of the medication review process phases most usually performed. Incomplete questions were analyzed as such (information non available).

For the analysis, the reported CMR practices were categorized into three categories according to their comprehensiveness by using Clyne et al's typology [34]. First, the respondents were asked to categorize their CMR practice according to Clyne et al'due south typology by selecting an option from the structured list that best fitted the purpose of their practice (Additional file 1). To validate the categorization, the researchers independently performed another categorization by using all the provided data on the exercise, with a special emphasis on patient data sources, medications, patient interest and objectives of the review. Active patient involvement was required in blazon 3 practices (clinical medication review). In Clyne et al., the minimum criteria for agile patient involvement is that the patient is nowadays [34]. Our estimation of this criteria is that at minimum the patient should be interviewed. Finally, the categorization performed by the researcher was compared with that performed by the respondent. In cases of discrepancies, the categorization past the researcher was used.

Results

Medication review practices

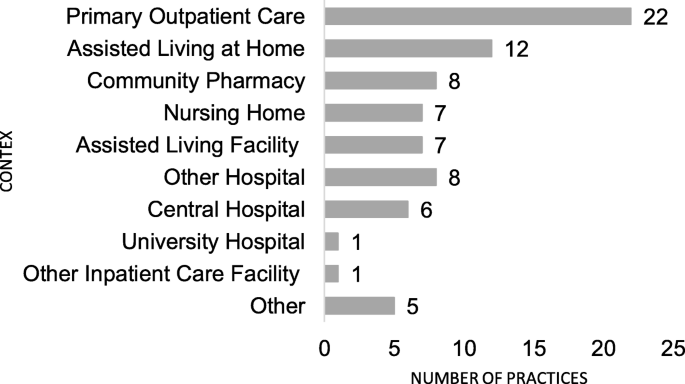

In total, 43 CMR practices were identified past 38 respondents, of which 22 (51%) practices were designed for older people in master intendance (Fig. 1). Most all practices (north = 42/43) were established after the yr 2005. The majority (n = xxx, 70%) of the practices were comprehensive clinical medication reviews, involving patients in the review process and concentrating on clinical evaluation rather than reviewing medication lists. Seven (16%) of the practices were concordance and compliance reviews, and two (5%) were prescription reviews. It was not possible to categorize four (ix%) of the practices according to Clyne el al's typology [34], considering they were comprised of but ane stage of the review process or described apply of a tool in reviewing medications (for example, a tool to identify patients with gamble factors for medication-related problems). In xl out of 43 practices (93%) the respondent and the researcher agreed on the categorization of the practice: 3 practices (seven%) were graded by the respondents to be more comprehensive than did the researchers. The majority of the practices (n = 29, 67%) were targeted to outpatients, 8 (xix%) to inpatients and half-dozen (xiv%) to both types of patients. 15 of the practices (35%) were used in at least two dissimilar health care contexts (Fig. 1). Of the practices, 28 (65%) were government or municipality funded. Nearly of the practices (north = 31, 72%) were established between 2013 and 2015. Xviii of them (42%), were in routine employ, 18 (42%) were in a airplane pilot phase, 4 (nine%) under development, and one (2%) was in a planning phase.

Health care context of the reported collaborative medication review practices for older adults in 2015 (n = 43, 15 of the practices were conducted in multiple contexts)

Identification of patients with medication-related issues

A checklist with criteria was used in 19 (44%) of the practices to identify patients with medication-related problems. Twelve of them included explicit criteria that varied considerably between practices (Tabular array ane). The commonly used criteria were 1) polypharmacy expressed as number of medicines in use (n = 6), 2) number of falls (northward = 5), and 3) renal dysfunction (n = 5). Information about the identified patient with medication-related issues was transmitted via electronic health records (EHRs) (n = 11, 26%), interpersonal communication (n = 7, sixteen%) or straight contact with the physician via different communication means, (n = six, 14%). Most ordinarily, patients with medication-related problems were identified by nurses (northward = 39, 91%), pharmacists (northward = 32, 74%) and physicians (due north = 28, 65%).

Conducting collaborative medication reviews

CMRs were nearly commonly conducted at the signal of prescribing (due north = ten, 23%), on the ward (n = 10, 23%), or in assisted living (due north = v, 12%). Nurses (n = twoscore, 93%) and physicians (north = 39, 91%) were involved in most of the practices. Other health care professionals involved were pharmacists (n = 35, 81%), applied nurses (a championship in Republic of finland for nurses having a three-year vocational pedagogy that focuses on supportive and technical nursing) (n = 23, 53%), and physiotherapists (n = 6, 14%). In half of the practices, pharmacist reviewed medications (n = 22, 51%) (Table 2). Nurses had central contribution throughout the reviewing procedure. About of the responsibilities was shared and conducted collaboratively. Phases that were acted alone past particular professionals were well-nigh unremarkably decisions on medication changes by physicians (n = 17, 40%), follow-up of the medication changes by practical nurses (northward = 8, 19%), and medication reviews past pharmacists (northward = 20, 47%).

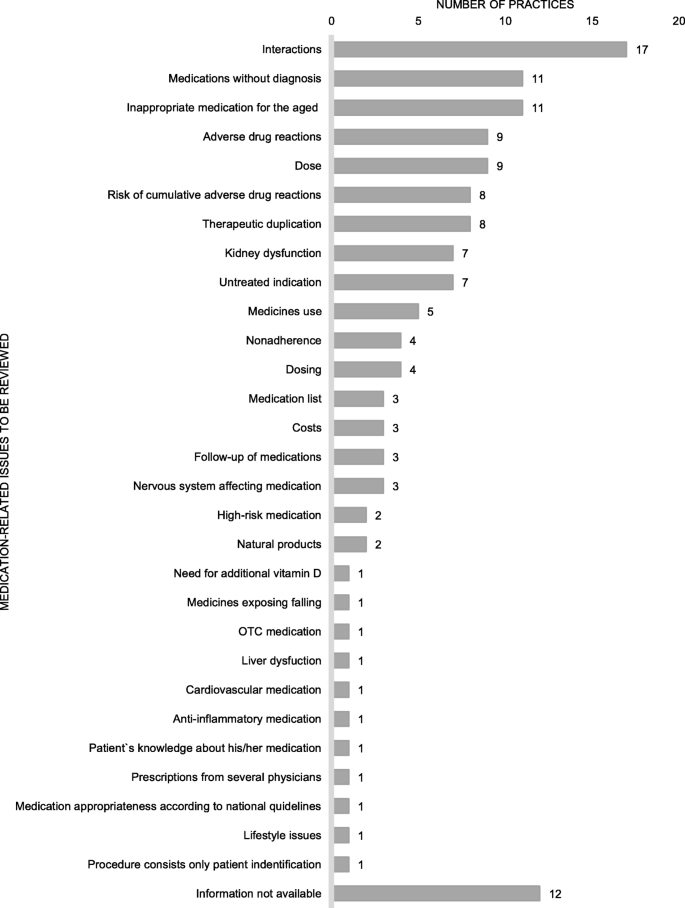

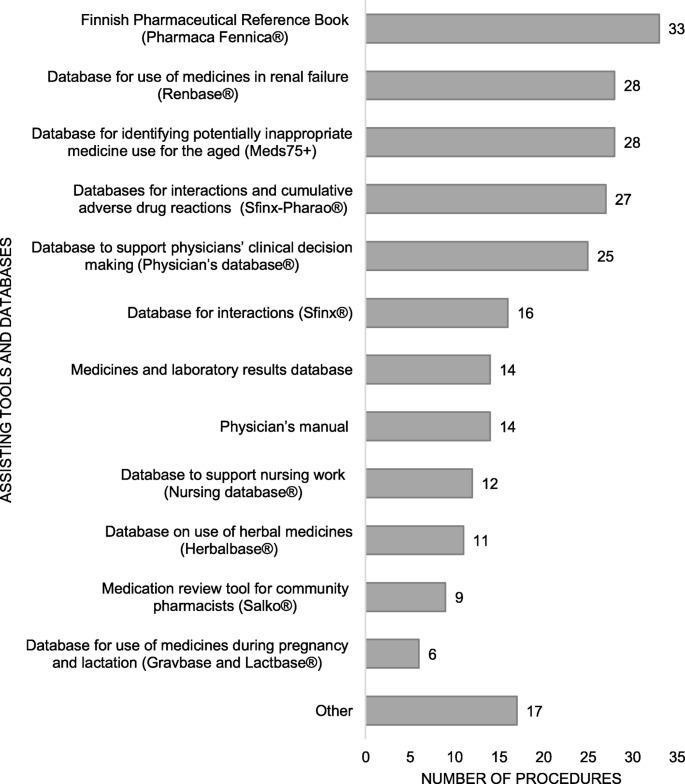

CMRs about commonly focused on interactions, medications without diagnosis, and potentially inappropriate medications for older adults (PIM'south) (Fig. 2). Few practices considered appropriateness of the medication according to national electric current care guidelines, self-medication and use of natural products, or patient adherence to the medications. Electronic National Reference Book and databases for medicine use in renal dysfunction, for identifying potentially inappropriate medicine employ for the aged, interactions and adverse drug reactions, and the clinical decision-back up organization for physicians were frequently used to assist in reviewing medications (Fig. 3). Generally, more than one tool or database was utilized (n = 35, 81%), and the most common combination was Electronic National Reference Book and database for medicine employ in renal failure (n = 28, 65%).

Medication-related bug to be reviewed in the practices (practices n = 43, several aspects tin can be reviewed in the same medication review)

Assisting tools and databases in medication review practices (n = 43), more than ane tool and/or database tin can exist used in the aforementioned do

Near normally, the medico decided on medication changes after hearing other health care professionals (n = 24, 56%), or decisions were made in a squad meeting (due north = 19, 44%). Decisions were seldom fabricated together with the nurse and the doc (due north = i, ii%), in the ward (due north = one, ii%), or via remote conferencing (n = 1, 2%).

Information was transferred betwixt healthcare professionals or organizations most ordinarily via patient information systems (n = 19, 44%), as a written report (northward = 9, 21%), past telephone (n = 7, 16%), through conversation (n = 7, 16%) or electronically (north = seven, sixteen%). Patients received information near normally equally a written summary (northward = 16, 37%) or via chat (n = 15, 35%) with one or more wellness care professionals.

Patient interest

Patients were actively involved in 32 (74%) of the CMR practices inventoried, mostly equally a source of information via patient interview (north = 27, 63%), but seldom in the implementation of medication changes. A medication intendance plan was discussed together with the patient in 17 practices (twoscore%), and in 8 practices (19%) patients updated the medication list by themselves. A habitation visit was included in 15 practices (35%). Proxies were involved in the process most ordinarily as a source of patient information (north = 18, 42%), or data was relayed to them near the patient'due south intendance (n = 7, sixteen%).

Follow-up

Medication care plans were established routinely equally usual care systematically to all or selected patient groups in 11 of the practices (26%) or to some patients in 11 of the practices (26%). The medication list was reconciled as usual and customary care systematically to all or selected patient groups in 15 of the practices (35%) or to some patients in four of the practices (9%) routinely. In about half of the practices (n = xix, 44%), data was missing concerning the means in which the effects of the medication changes were followed up. When reported, (n = 24, 56%), furnishings were most unremarkably followed upwards in a routine control (n = 9, 21%) or in a split up follow-up appointment (northward = 6, 14%). Information about follow-ups was registered into patient information systems (n = 6, 14%) or into a care program (due north = 3, 7%).

Discussion

This study was the first inventory of CMR practices in Republic of finland. The inventory identified a remarkable number of practices developed within a decade, of which the majority were comprehensive clinical medication reviews. Nearly half of the practices were in routine use in various healthcare contexts in 2015, which may point that CMRs are becoming a office of usual and customary care. This inventory provides valuable information for further optimization of the existing practices and development of the new ones that were numerous under way in 2015 when the inventory was conducted. The inventory describes practices and the manner in which they take identify in actual patient intendance and in more detail than previous literature [4,v,6,7,8,9, 37, 38]. Based on the report findings, CMR practice problems requiring more than attention and standardization are: 1) criteria used for identifying older adults needing medication review, ii) enhancing patient interest in implementing the therapeutic programme, specially when medication changes are implemented, and 3) enhancing follow-up of medication changes.

Potentially greater proportions of comprehensive CMR practices reported in Republic of finland compared with other countries may be due to their origin in such practices every bit Dwelling Medicines Reviews (HMRs) in Australia [10, 13, 19, 27]. Benchmarking and cooperating with other countries having more advanced CMR practices were instrumental for getting started by learning from their experiences. For instance, the structure of Republic of finland's CMR process was inspired from Australia's HMR program [27]. The HMR process is initiated by the physician and conducted equally a teamwork. In a home visit the pharmacist reviews the patient's medications. The findings are discussed during a collaborative case conference. The patient is central in the development and implementation of the medication management program aiming to maximize the patient's benefits from the medications and prevent medication-related issues.

The development of the first Finnish comprehensive medication review procedures was initiated in 2005 as part of a long-term continuing teaching (1.5 years alongside work) providing accredited medication review competence for practicing pharmacists [19, 27]. The pedagogy revolves around patient-oriented pharmacotherapy with special focus on geriatric intendance, medication review principles and interprofessional collaboration. In many other countries, the development of practices has begun from medication list reviews (i.e. prescription reviews), which take been extended to more than comprehensive procedures [13]. Given that a broad variety of CMR practices was identified, national standardization might be considered to ensure quality in patient care. However, information technology should be recognized that different practices are needed in different contexts with varying resources and patients needs [30, 39].

Compared with CMR practices in other countries, nurses, especially practical nurses, seem to have a stronger role in Finland [iv,5,6,7,8,9,x]. Applied nurses' contribution was peculiarly strong in identifying older people needing medication reviews, simply they too contributed commonly by counseling patients on medication changes and following up their implementation. This may be due to the fact that practical nurses are the health care providers working virtually closely with older patients in primary care in Finland, for example in home care and assisted living. If they find whatsoever bug with their clients' medications, they are expected to study their findings to the nurse, and when needed, involve the physician in solving the bug [40]. Our findings point that likewise pharmacists were quite often involved in identifying patients with medication-related problems and reviewing their medications. This has become more than common since medication review accreditation training was started for pharmacists [41]. Withal, the local medication management processes need to exist improve coordinated to make better use of the existing resources [30, 31, 33].

The criteria for identifying older patients with medication-related problems were missing from the majority (72%) of the reported practices. Just 12 practices included the criteria which were commonly 1) the number of medicines in use, 2) falls and 3) renal dysfunction. In addition to these, a long and lengthened listing of individual criteria, each of them appearing in one of the procedures was found. This suggests that consensus should be reached on issues contributing to clinically pregnant medication-related problems in older adults. Evidence on advisable criteria is still scarce, but information technology appears that for example the number of medicines in utilize is not a priority benchmark although widely used [forty]. A recent airplane pilot study suggests that priority criteria should include symptoms that may be drug-induced such every bit drowsiness, skin rash or crawling, dizziness and urination problems; having more than than one doctor involved in patient care; and more than than i fall in the past 12 months [40]. Further research is needed on the identification criteria to find the older patients benefitting the well-nigh from CMRs.

In this inventory, patients were reported to be involved in the implementation of the medication changes, not only serving equally a source of background data, in several practices at different types of the CMRs. Information technology is essential to continue emphasizing and facilitating patient involvement throughout the medication review procedure because involving patients in healthcare determination-making has found to pb to enhanced adherence and potentially amend treatment outcomes [42]. This empowering tendency has been highlighted in the medicines policy in Finland and elsewhere in the EU [43, 44].

The reports provided trivial information about follow-ups on medication changes. Medication review may take little event on patient intendance if the follow-upward is missing or is inadequate, or there is no agreement near the implementation of the medication changes to patient care. Follow-upwardly of medication changes is an expanse for improvement in Republic of finland, merely likely for other countries, besides [10].

Limitations

While the inventory was derived from practices in Republic of finland, lessons learned tin can be worthy of consideration by practitioners and policymakers in other countries. Due to the snowballing approach used, this inventory does not necessarily cover all CMR practices in Republic of finland at the fourth dimension of the inventory. However, there were rich information received via this method from various CMR practices in different healthcare settings.

The data reflect evolution of CMR practices by 2015. Since then, the number and variety of practices have evolved, perchance in a growing pace considering CMRs were recommended by the Government Program in 2015 for mitigating health challenges posed past the rapidly crumbling population. Further research is recommended to follow up the well-nigh contempo developments within the concluding 4 years. Future research is also recommended to model interactions within the CMR practices and define event variables and their predictors.

The content validity of the inventory instrument was carefully examined; however, true construct validity was not established. Although open-ended questions enabled the informants to describe practices in their own words, this might have increased response burden to some informants, thereby influencing accurateness and completeness of their responses.

Applied implications

This kickoff inventory conducted in 2015 of Finnish CMR practices provides valuable insights for their ongoing evolution. Attending should exist paid to option criteria for patients, patient involvement, and implementing and post-obit upward medication changes if recommended as a issue of the medication review. Information from this study can be used across Finland for implementing new CMR practices in other countries. More studies demand to be conducted on patient identification and follow-up to deepen understanding of these practices.

Conclusions

Different types of CMR practices in varying health care settings were bachelor and in routine use in Finland in 2015, the bulk beingness designed for primary outpatient care and for comprehensive reviews of older patients' medications. Even though practices might benefit from national standardization, allowing for flexibility in their customization co-ordinate to context, medical and patient needs and bachelor resources is of import for optimizing care.

Availability of data and materials

The information that support the findings of this study are bachelor on asking from the corresponding author AK. The data are not publicly bachelor due to them containing information that could compromise enquiry participant privacy.

Abbreviations

- AFP:

-

The Association of Finnish Pharmacies

- CMR:

-

Collaborative Medication Review

- Eu:

-

European Matrimony

- FIMEA:

-

Finnish Medicines Agency

- ILMA:

-

The enquiry project on medicines optimization for older adults

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- PIM'due south:

-

Potentially inappropriate medications for older adults

- SPSS-21:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- U.k.:

-

Uk

- USA:

-

United states

References

-

Saastamoinen LK, Verho J. Register-based indicators for potentially inappropriate medication in loftier-cost patients with excessive polypharmacy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(half dozen):610–viii.

-

National Constitute for Wellness and Care Excellence (NICE). Medicines optimisation. 2016. Quality Standard. nice.org.great britain/guidance/qs120 © Dainty. .https://world wide web.prissy.org.uk/guidance/qs120/resource/medicines-optimisation-pdf-75545351857861Accessed 3 October 2018.

-

Peterson C, Gustafsson Yard. Characterisation of drug-related issues and associated factors at a clinical pharmacist service-naive Hospital in Northern Sweden. Drugs Existent World Outcomes. 2017;4(2):97–107.

-

Kaur South, Mitchell G, Vitetta L, Roberts MS. Interventions that can reduce inappropriate prescribing in the elderly: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(12):1013–28.

-

Kwint HF, Bermingham Fifty, Faber A, Gussekloo J, Bouvy ML. The relationship between the extent of collaboration of general practitioners and pharmacists and the implementation of recommendations arising from medication review: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;thirty(2):91–102.

-

Lamantia MA, Scheunemann LP, Viera AJ, Busby-Whitehead J, Hanson LC. Interventions to improve transitional care betwixt nursing homes and hospitals: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(four):777–82.

-

Loganathan One thousand, Singh S, Franklin BD, Bottle A, Majeed A. Interventions to optimise prescribing in intendance homes: systematic review. Age Ageing. 2011;forty(2):150–62.

-

Verrue CL, Petrovic M, Mehuys E, Remon JP, Vander SR. Pharmacists' interventions for optimization of medication utilize in nursing homes: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(1):37–49.

-

Patterson SM, Cadogan CA, Kerse N, Cardwell CR, Bradley MC, Ryan C, et al. Interventions to improve the advisable use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;10:e009235.

-

Kiiski A, Kallio Southward, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä M, Kumpusalo-Vauhkonen A, Järvensivu T, Airaksinen M, et al. Interdisciplinary collaboration models to rationalize the medications of the elderly – systematic review. Reports and Memorandums of the Ministry building of Social Affairs and Health, vol. 12; 2016. http://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/74808/RAP-2016-12-iakkaiden-50%C3%A4%C3%A4kehoidon-j%C3%A4rkeist%C3%A4minen.pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2018

-

Basger BJ, Moles RJ, Chen TF. Application of drug-related problem (DRP) classification systems: a review of the literature. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70(vii):799–815.

-

Bryant LJ, Coster G, Take chances GD, McCormick RN. The general practitioner-pharmacist collaboration (GPPC) report: a randomised controlled trial of clinical medication reviews in community pharmacy. Int J Pharm Pract. 2011;19(2):94–105.

-

Bulajeva A, Labberton L, Leikola Due south, Pohjanoksa-Mantyla M, Geurts MM, de Gier JJ, et al. Medication review practices in European countries. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2014;10(5):731–40.

-

Elliott RA, Martinac K, Campbell S, Thorn J, Woodward MC. Pharmacist-led medication review to identify medication-related problems in older people referred to an aged intendance cess squad: a randomized comparative study. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(7):593–605.

-

Fis T, Meinke-Franze C, van den Berg Due north, Hoffmann Due west. Effects of a three party healthcare network on the incidence levels of drug related problems. Int J Pharm Pract. 2013;35(5):763–71.

-

Fletcher J, Hogg W, Farrell B, Woodend Yard, Dahrouge S, Lemelin J, et al. Effect of nurse practitioner and chemist counseling on inappropriate medication use in family do. Can Fam Doc. 2012;58(8):862–8.

-

Freeman C, Cottrell WN, Kyle G, Williams I, Nissen L. Does a primary care exercise pharmacist improve the timeliness and completion of medication management reviews? Int J Pharm Pract. 2012;20(6):395–401.

-

Hellström LM, Höglund P, Bondesson Å, Petersson Yard, Eriksson T. Clinical implementation of systematic medication reconciliation and review as part of the Lund integrated medicines management model - bear upon on all-cause emergency department revisits. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2012;37(6):686–92.

-

Leikola South, Tuomainen L, Peura S, Laurikainen A, Lyles A, Savela Eastward, et al. Comprehensive medication review: development of a collaborative procedure. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34(four):510–4.

-

Milos V, Rekman E, Bondesson A, Eriksson T, Jakobsson U, Westerlund T, et al. Improving the quality of pharmacotherapy in elderly chief care patients through medication reviews: a randomised controlled report. Drugs Aging. 2013;thirty(four):235–46.

-

van den Bemt PM, van der Schrieck-de Loos EM, van der Linden C, Theeuwes AM, Pol AG, Dutch CBOWHO. High 5s report group. Effect of medication reconciliation on unintentional medication discrepancies in acute hospital admissions of elderly adults: a multicenter study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(8):1262–8.

-

Blenkinsopp A, Bond C, Raynor DK. Medication reviews. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74(iv):573–fourscore.

-

The Ministry of Social Affairs and Wellness, Finland. Safe pharmacotherapy amid the aged: obligations for the municipalities [article in Finnish]. Publications of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. 2009. p. ten. https://stm.fi/artikkeli/-/asset_publisher/trygg-lakemedelsbehandling-for-aldre-kommunernas-forpliktelser. Accessed three October 2018.

-

Earth Health Arrangement (WHO). Globe Written report on Ageing and Wellness. 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/186463/9789240694811_eng.pdf;jsessionid=F8FC5A2D6D7597BE495E8F5390B0D068?sequence=one. Accessed 3 Oct 2018.

-

Government of Republic of finland. Finland, a state of solutions. Strategic Programme of Prime number Minister Juha Sipilä's Regime 29 May 2015: Government publications 12/2015. 2015. https://valtioneuvosto.fi/documents/10184/1427398/Hallitusohjelma_27052015_final_EN.pdf. Accessed 3 October 2018.

-

Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. Implementation plan of the rational pharmacotherapy: https://stm.fi/rationaalinen-laakehoito?p_p_id=56_INSTANCE_7SjjYVdYeJHp&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view&p_p_col_id=column-2&p_p_col_count=three&_56_INSTANCE_7SjjYVdYeJHp_languageId=en_US. Accessed three Oct 2018.

-

Leikola SN, Tuomainen L, Ovaskainen H, Peura S, Sevon-Vilkman Due north, Tanskanen P, et al. Continuing education grade to achieve collaborative comprehensive medication review competencies. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(half-dozen):108.

-

Schepel 50, Aronpuro Chiliad, Kvarnström G, Holmström A-R, Lehtonen 50, Lapatto-Reiniluoto O, et al. Strategies for improving medication rubber in hospitals: evolution of clinical chemist's services. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2019 xv(7):873-82.

-

Schepel L, Lehtonen L, Airaksinen M, Ojala R, Ahonen J, Lapatto-Reiniluoto O. Medication reconciliation and review for older emergency patients' requires improvement in Finland. Int J Gamble Saf Med. 2019;30(1):nineteen–31.

-

Toivo T, Dimitrow M, Puustinen J, Savela Due east, Pelkonen G, Kiuru V, et al. Analogous resource for prospective medication adventure direction of older dwelling house care clients in chief care: procedure development and RCT study design for demonstrating its effectiveness. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:74.

-

Merikoski M, Jyrkkä J, Auvinen 1000, Enlund H, Kumpusalo-Vauhkonen A, Liukkonen T et al. The Finnish Interprofessional Medication Cess (FIMA). Effects on medication, functional ca-pacity, quality of life and use of health and home care services in home care patients Reports and Memorandums of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Wellness 2017:34. 2017. http://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/80566/Rap_17_34.pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2018.

-

Kallio Southward, Kiiski A, Airaksinen Thousand, Mäntylä A, Kumpusalo-Vauhkonen A, Järvensivu T, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä M. Community Pharmacists' contribution to medication reviews for older adults: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(eight):1613–20.

-

Kallio S, Kumpusalo-Vauhkonen A, Jarvensivu T, Mantyla A, Pohjanoksa-Mantyla M, Airaksinen Thousand. Towards interprofessional networking in medication management of the anile: current challenges and potential solutions in Finland. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2016;8:1–ix.

-

Clyne W, Blenkinsopp A, Seal R. A Guide to Medication Review 2008. 2008. Bachelor at: http://www2.cff.org.br/userfiles/52%twenty-%20CLYNE%20W%20A%20guide%20to%20medication%20review%202008.pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2018.

-

Lavrakas P. Encyclopedia of survey research methods. Chiliad Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2008.

-

Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;xv(three):398–405.

-

Castelino RL, Bajorek BV, Chen TF. Targeting suboptimal prescribing in the elderly: a review of the impact of chemist's services. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(6):1096–106.

-

Jokanovic N, Tan EC, Sudhakaran Due south, Kirkpatrick CM, Dooley MJ, Ryan-Atwood TE, et al. Pharmacist-led medication review in customs settings: an overview of systematic reviews. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2017;13(4):661–85.

-

Sinnemaki J, Saastamoinen LK, Hannula S, Peura Due south, Airaksinen M. Starting an automated dose dispensing service provided past community pharmacies in Finland. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36(2):345–51.

-

Dimitrow M. Evolution and Validation of a Drug-related Problem Take chances Assessment Tool For Employ by Applied Nurses Working With Community-Abode Anile, University of Helsinki, Doctoral Thesis. 2016. https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/167914/Developm.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed iii Oct 2018.

-

Kumpusalo-Vauhkonen A, Järvensivu T, Mäntylä A. A multidisciplinary approach to promoting sensible pharmacotherapy among aged persons – a national assessment and recommendations. Finnish Medicines Bureau Fimea. Series Publication Fimea Develops, Assesses and Informs 8/2016. 63 p. ISBN 978–952-5624-65-6 (pdf). https://www.fimea.fi/documents/160140/1153780/KAI+8_2016.pdf/7acaeff3-999e-4749-8a47-36fbcb4db8b7. Accessed three Oct 2018.

-

Mohammed MA, Moles RJ, Chen TF. Medication-related burden and patients' lived feel with medicine: a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e010035–2015-010035.

-

Earth Health Organisation (WHO). Continuity and Modify: Implementing the 3rd WHO Medicines Strategy - 2008-2013, WHO/EMP/2009.1. 2010. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70301/WHO_EMP_2009.1_eng.pdf?sequence=one&isAllowed=y. Accessed iii October 2018.

-

Ministry of Social Affairs and Wellness. Medicines policy 2020: Publications of the Ministry of Social Diplomacy and Health:2011:10. http://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/71811/URN%3aNBN%3afi-fe201504226140.pdf?sequence=one&isAllowed=y.

Acknowledgements

The authors would admit all the respondents who actively reported their practices, all the experts involved in forming the inventory instrument, especially Maarit Dimitrow, PhD and Ercan Celikkayalar MSc (Pharm), for valuable comments. Nosotros desire to acknowledge Chelsea Schneider who gave valuable comments for the manuscript.

Funding

The research design and data collection was conducted during the funding from The Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. The funding body paid the primary researchers bacon. The funding torso has no part in the pattern of the study and collection, assay, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Writer data

Affiliations

Contributions

AK has fabricated substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation of data and drafting the manuscript. MA has fabricated substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of information, drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. AM has fabricated substantial contributions to formulation and blueprint, conquering of data and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. SD has fabricated substantial contributions to analysis and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript critically for of import intellectual content. AK-Five has made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. TJ has made substantial contributions to conception and design, conquering of data and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. MP-Grand has made substantial contributions to formulation and design, acquisition of data, assay and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have given final approval of the version to exist published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of whatever function of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In Finland, anonymous questionnaires are exempt from ethical approving [1]. The study followed the national upstanding guidelines for researchers. Responding to the survey was considered as giving informed consent.

Finnish advisory board on enquiry integrity: ethical principles of inquiry in the humanities and social and behavioral sciences and proposals for ethical review. 2009 https://www.tenk.fi/en/ethical-review-in-finlandAccessed xv Nov 2017

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatever medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were fabricated. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/nix/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Kiiski, A., Airaksinen, M., Mäntylä, A. et al. An inventory of collaborative medication reviews for older adults - evolution of practices. BMC Geriatr nineteen, 321 (2019). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12877-019-1317-6

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12877-019-1317-6

Keywords

- Collaborative medication review

- Comprehensive medication review

- Concordance and compliance review

- Adherence review

- Prescription review

- Medicines optimization

- Older adults

cheathammilitaidele.blogspot.com

Source: https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12877-019-1317-6

0 Response to "Why Its Imoortant for Seniors to Have Medication Review"

Post a Comment